Should you be concerned about dizziness?

A visit to the office and balance lab of otolaryngologist Craig Jones, MD gives one a whole new perspective on disorders that can affect balance.

In conversations with friends and family, almost everyone would probably comment that at some point in their life they felt dizzy or had experienced vertigo. But do we really know what these terms mean, and how they play a role in diagnosis and treatment of various inner ear and balance disorders known as vestibular disorders?

Vestibular disorders are diseases or injuries that cause damage to parts of the inner ear and brain that process sensory information involved with controlling balance and eye movements, according to the Vestibular Disorders Association (VEDA).

It turns out that the terms ‘dizziness’ and ‘vertigo’, which many patients use to describe their symptoms for these disorders, don’t give a clear idea of what they are experiencing. They mean something different to everyone. Dr. Jones stressed the importance of giving an accurate description of symptoms to your doctor to help pinpoint the cause and diagnosis.

“It’s tricky because the problem with dizziness is that most patients come in to the office and they use words they don’t necessarily mean,” he said. “For example, they may say they have vertigo. They may have heard it from a friend or at the hospital thinking that vertigo means feeling off-balance, when it is actually a sense of spinning and is often accompanied by nausea.”

With dizziness, patients may feel like they are falling over or losing their step a little bit, added Elizabeth A. Flynn, Au.D, CCC-A, an audiologist in Dr. Jones’s office.

Describing Symptoms A Must

Dr. Jones and his staff ask patients to describe whatever they feel and give them details about what they are experiencing.

An in-depth description of the symptoms helps Dr. Jones diagnose the problem.

“If a patient comes in and says that they are dizzy and then I ask them more details and they say they feel like they are going to pass out, then that’s really more cardiovascular, not an ear problem,” said Dr. Jones. He would then refer them to a cardiologist.

“Complaints of feeling light-headed is one of the harder ones because it doesn’t fit into any category and in those cases, we sometimes do testing because we we’re trying to figure if there is evidence of an ear problem,” said Dr. Jones.

Once Dr. Jones gets a clear picture of the patient’s symptoms and history, he can diagnose vestibular disorders in 90 percent of the cases and begin treatment.

“If I am not 100 percent certain what they have or they have a diagnosis that I feel testing might help me to support then I will go ahead and order the testing in our lab. Frequently, it’s like putting a puzzle together,” he said.

Vestibular Disorders

Vestibular disorders affect 35.4 percent of adults in the United States aged 40 years and older, or approximately 69 million Americans, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The most common vestibular disorder is Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) according to VEDA. This occurs when tiny crystals of calcium carbonate detach from the otolithic membrane in the inner ear and collect in one of the semicircular canals in the ear. They clump together and when your head moves, the crystals shift, causing a false signal to be sent to the brain about your head’s movement.

Your brain thinks the head is moving when it’s not. It can cause you to have vertigo, involuntary eye movements, difficulty concentrating and nausea.

Other disorders include Meniere’s Disease, Vestibular Neuritis and Labyrinthitis, and Vestibular Migraine.

The balance system in the body is really comprised of three systems, said Flynn.

They are:

- Inner Ear

- Our visual system, our eyes

- Our proprioceptive system

These systems help to control and maintain balance by all working together. “This is our body’s ability to know where it is in space,” she said.

The vestibular system in the inner ear maintains motion, equilibrium, and spacial orientation.

Testing in the Lab

“There is an extensive battery of tests that takes about two hours,” Flynn said. “We never make a diagnosis on one test or another, we look at everything together.”

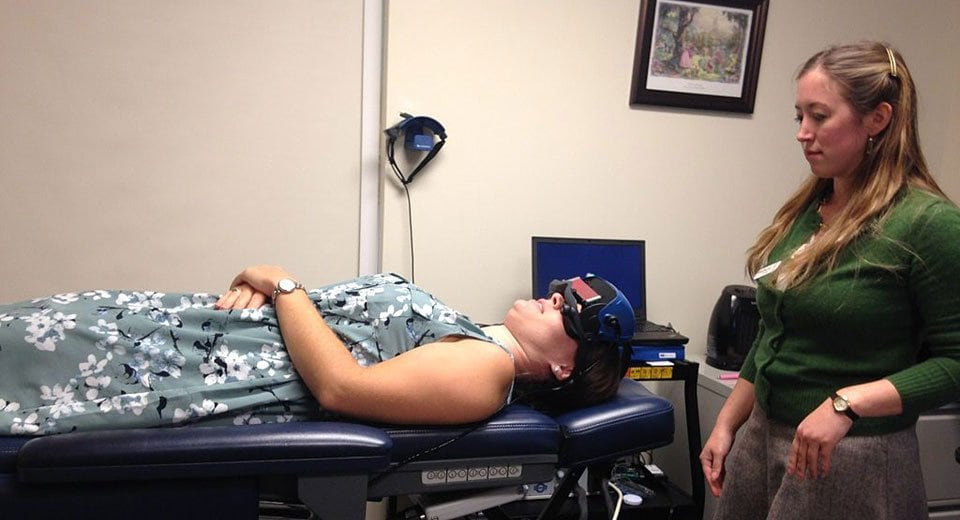

She uses Videonystagmography (VNG), which measures eye movements as part of the evaluation for vestibular problems and can indicate neurological problems. The patient wears a pair of goggles during the tests that contain cameras to watch eye movements.

Flynn interprets the results and forwards a report to Dr. Jones that he will share with patients at their two-week follow-up appointment.

“The nice thing about the testing is that it gives us quantitative data and is not just saying that something doesn’t seem quite right,” said Dr. Jones. “Patients can come back to be re-tested if necessary and we compare those results with prior results.”

A clear picture of the symptoms helps Dr. Jones to determine what is going on with the patient. Around 90 percent of the patients he sees can be diagnosed based on the medical history.

Once he has the results of the tests, he can decide on a treatment plan.